James Roosevelt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Roosevelt II (December 23, 1907 – August 13, 1991) was an American businessman, Marine, activist, and

"The Secret Boozy Deals of a Kennedy, a Churchill, and a Roosevelt"

''

Accessed June 13, 2013 In 1954, Roosevelt was elected U.S. Representative from

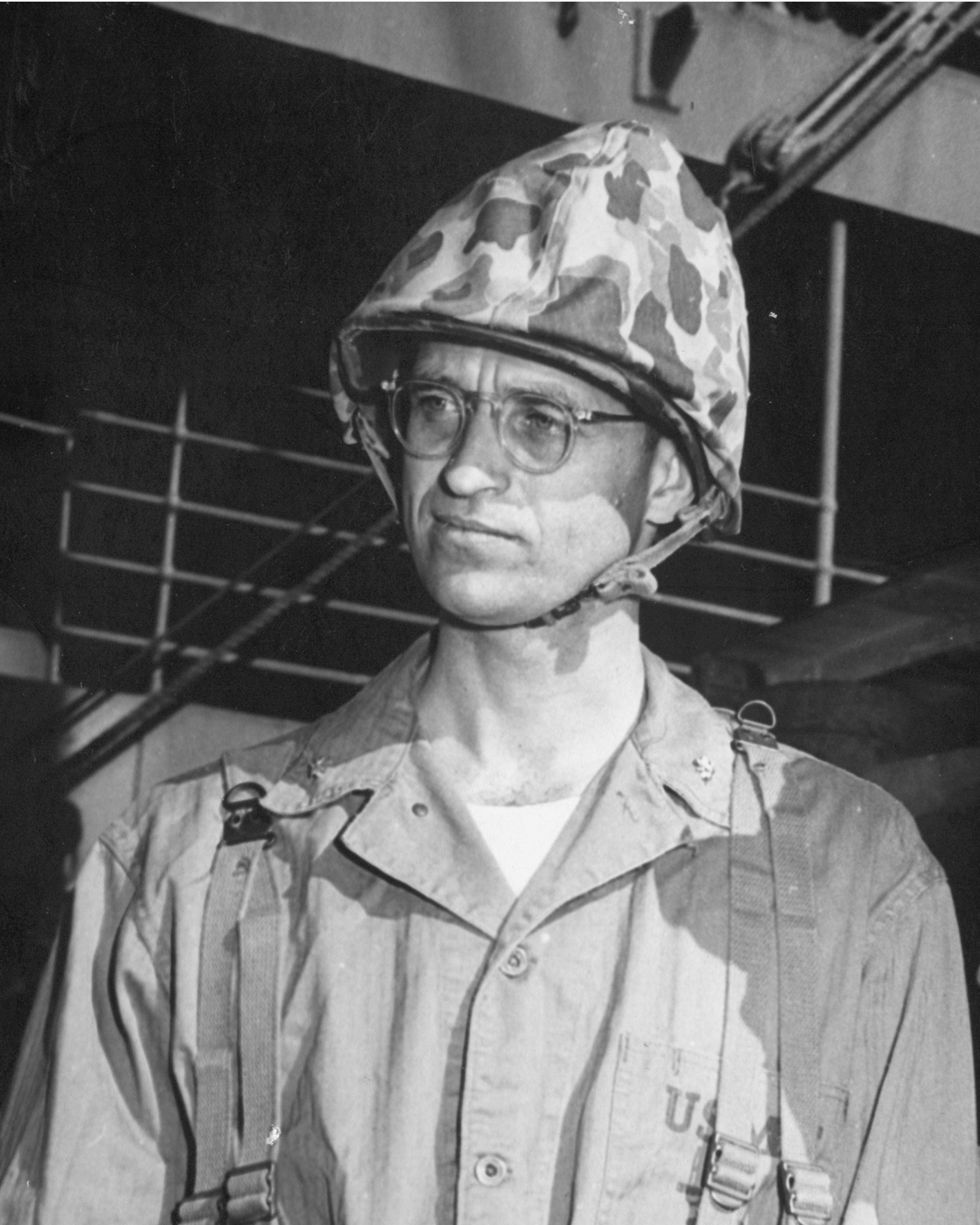

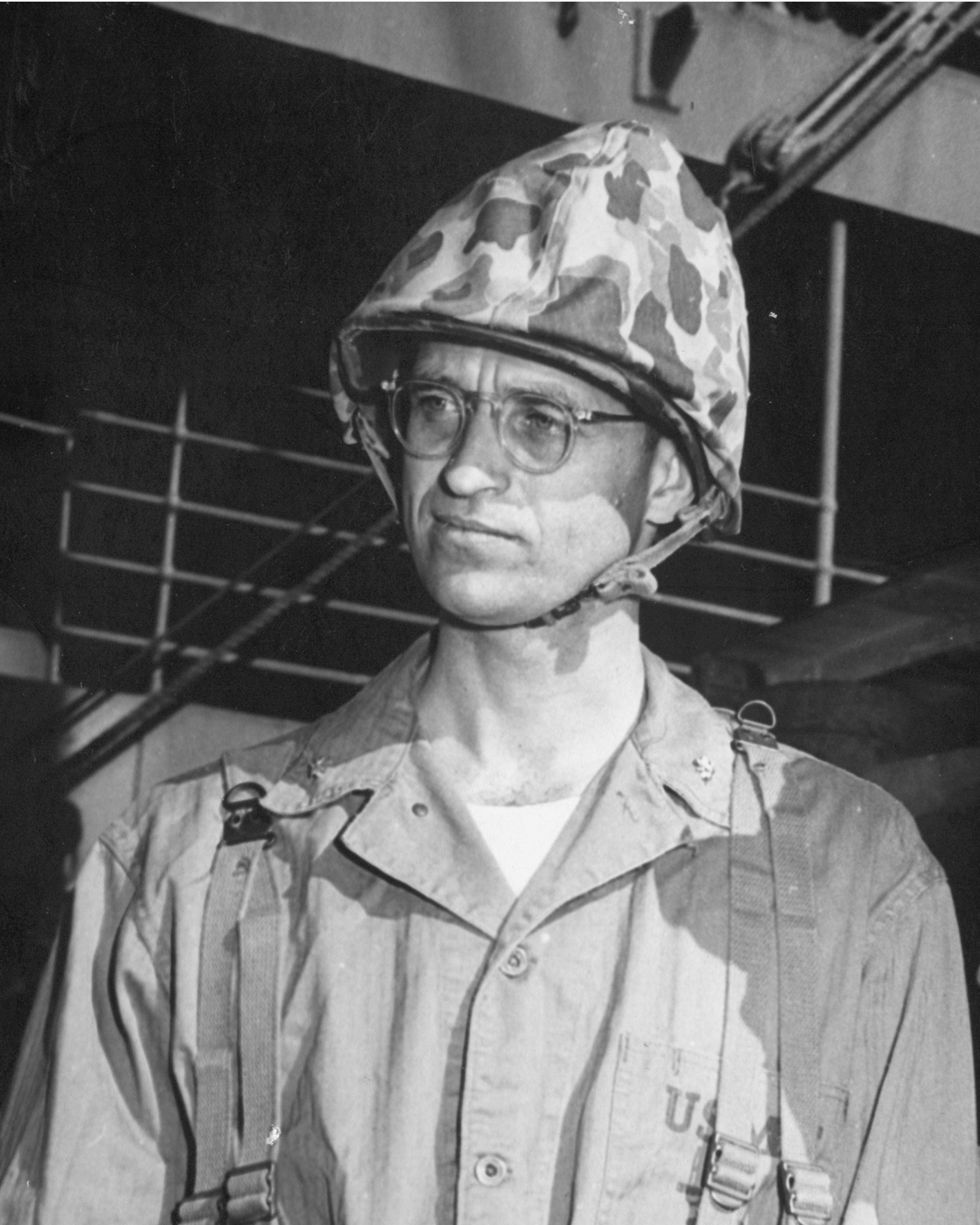

Brigadier General James Roosevelt, USMCR

''Who's Who in Marine Corps History'', History Division, United States Marine Corps

Retrieved on 2008-07-08

– Marine Corps Legacy Museum * Hansen, Chris. ''Enfant Terrible: The Times and Schemes of General Elliott Roosevelt.'' Tucson: Able Baker Press, 2012. * Roosevelt, James. ''Affectionately, F.D.R.'' Hearst/Avon Division, New York, 1959. (w. Sidney Shalett) * Roosevelt, James. ''My Parents: A Differing View''. Playboy Press, Chicago, 1976. (w. Bill Libby)

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Museum

*

held b

Special Collection & Archives

Nimitz Library

at th

United States Naval Academy

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Roosevelt, James 1907 births 1991 deaths American film producers 20th-century American memoirists 20th-century American novelists United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II American people of Dutch descent American people of Scottish descent Bulloch family Burials at Pacific View Memorial Park Children of presidents of the United States Delano family Harvard College alumni Marine Raiders Livingston family Members of the United States House of Representatives from California New York (state) Democrats Personal secretaries to the President of the United States Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Silver Star

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

politician. The eldest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, he served as an official Secretary to the President for his father and was later elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

representing California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, serving 5 terms from 1955 to 1965. He received the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

while serving as a Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

officer during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Early life

Roosevelt was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

at 123 East 36th Street. He was named after his grandfather on his father's side James Roosevelt I

James Roosevelt I (July 16, 1828 – December 8, 1900), known as "Squire James", was an American businessman, politician, horse breeder, and the father of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd president of the United States.

Early life

Roosevelt was bor ...

. He attended the Potomac School and St. Albans School in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and the Groton School

Groton School (founded as Groton School for Boys) is a private college-preparatory boarding school located in Groton, Massachusetts. Ranked as one of the top five boarding high schools in the United States in Niche (2021–2022), it is affiliated ...

in Massachusetts. At Groton, he rowed, played football, and was a prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

in his senior year. After graduating in 1926, he attended Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, where he rowed with the freshman and junior varsity crews. At Harvard, he followed family traditions in joining the Signet Society

The Signet Society of Harvard University was founded in 1870 by members of the class of 1871. The first president was Charles Joseph Bonaparte. It was, at first, dedicated to the production of literary work only, going so far as to exclude debate ...

and Hasty Pudding Club

The Hasty Pudding Club, often referred to simply as the Pudding, is a social club at Harvard University, and one of three sub-organizations that comprise the Hasty Pudding - Institute of 1770. The club's motto, ''Concordia Discors'' (discordant h ...

, of which both his father and his maternal granduncle and paternal fifth cousin once removed, President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, had been members, the Fly Club

The Fly Club is a final club, traditionally "punching" (inviting to stand for election) male undergraduates of Harvard College during their sophomore or junior year. Undergraduate and graduate members participate in club activities.

Founded 1836 ...

, which his father had joined, and the Institute of the 1770. He graduated from Harvard in 1930 and was elected permanent treasurer of his class.

After graduation, Roosevelt enrolled in the Boston University School of Law

Boston University School of Law (Boston Law or BU Law) is the law school of Boston University, a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. It is consistently ranked among the top law schools in the United States and considered an eli ...

. He also took a sales job with the firm of Victor De Gerard of Boston in 1930, remaining with that firm when it amalgamated with the John Paulding Meade Company which, in turn, amalgamated with O'Brion, Russell and Company in 1932. Roosevelt abandoned his law studies within a year due to his success at the firm. In 1932, he started his own insurance agency, Roosevelt & Sargent, in partnership with John A. Sargent. As president of Roosevelt & Sargent he made a substantial fortune (about $500,000 or more than $9 million in 2018 dollars). He resigned from the firm in 1937, when he officially went to work at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, but retained his half-ownership.

Roosevelt was elected a director of Boston Metropolitan Buildings, Inc. in 1933. He also served briefly as president of the National Grain Yeast Corporation from May to November 1935.

Politics and the White House

Roosevelt attended the 1924 Democratic National Convention where he served, in his words, as his father's "page and prop". In 1928, he and some Harvard classmates campaigned for Democratic presidential nomineeAl Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith (December 30, 1873 – October 4, 1944) was an American politician who served four terms as Governor of New York and was the Democratic Party's candidate for president in 1928.

The son of an Irish-American mother and a C ...

. In 1932, he headed his father's Massachusetts campaign and made about two hundred campaign speeches for that year. Though FDR lost the Massachusetts Democratic primary

This is a list of Democratic Party presidential primaries.

1912

This was the first time that candidates were chosen through primaries. New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson ran to become the nominee, and faced the opposition of Speaker of the Uni ...

to Smith, he easily carried Massachusetts in the November election. Roosevelt was viewed as his father's political deputy in Massachusetts, allocating patronage in alliance with Boston mayor James Michael Curley

James Michael Curley (November 20, 1874 – November 12, 1958) was an American Democratic politician from Boston, Massachusetts. He served four terms as mayor of Boston. He also served a single term as governor of Massachusetts, characterized ...

. He was also a delegate from Massachusetts to the Constitutional Convention for the repeal of Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

in 1933.

Roosevelt was a close protege of Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy (September 6, 1888 – November 18, 1969) was an American businessman, investor, and politician. He is known for his own political prominence as well as that of his children and was the patriarch of the Irish-American Ke ...

In fall 1933, the two journeyed to England to obtain the market in post-prohibition liquor imports.Maier, Thomas (October 21, 2014"The Secret Boozy Deals of a Kennedy, a Churchill, and a Roosevelt"

''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' Many of Roosevelt's controversial business ventures were aided by Kennedy, including his maritime insurance interests, and the National Grain Yeast Corp. affair (1933–35). Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. threatened to resign unless FDR forced his son to leave the latter company, suspected of being a front for bootlegging. Roosevelt was instrumental in securing Kennedy's appointment as ambassador to the United Kingdom.

In April 1936, Presidential Secretary Louis Howe

Louis McHenry Howe (January 14, 1871 – April 18, 1936) was an American reporter for the ''New York Herald'' best known for acting as an early political advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Born to a wealthy family in Indianapolis, ...

died. Roosevelt unofficially assumed Howe's duties. Soon after the 1936 re-election of his father, Roosevelt was given a direct commission as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in the Marine Corps, which caused public controversy for its obvious political implications. He accompanied his father to the Inter-American Conference

The Conferences of American States, commonly referred to as the Pan-American Conferences, were meetings of the Pan-American Union, an international organization for cooperation on trade. James G. Blaine, a United States politician, Secretary ...

at Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

in December as a military aide. On January 6, 1937, he was officially appointed "administrative assistant to the President"; on July 1, 1937, he was appointed secretary to the president. He was the White House coordinator for eighteen federal agencies by October 1937.

Roosevelt was considered among his father's most important counselors. ''Time'' magazine suggested he might be considered "Assistant President of the United States".

In July 1938, there were allegations that Roosevelt had used his political position to steer lucrative business to his insurance firm. He had to publish his income tax returns and denied these allegations in an NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

broadcast and an interview in ''Collier's

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened in 1905 to ''Collie ...

'' magazine. This became known as the ''Jimmy's Got It'' affair after Alva Johnston

Alva Johnston (August 1, 1888 – November 23, 1950) was an American journalist and biographer who won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1923.

Biography

Johnston was born in Sacramento, California.

He started out at the ''Sacramento Bee'' in 1 ...

's reportage in the ''Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

''. Roosevelt resigned from his White House position in November 1938.

Hollywood

After leaving the White House in November 1938, Roosevelt moved toHollywood, California

Hollywood is a neighborhood in the central region of Los Angeles, California. Its name has come to be a shorthand reference for the U.S. film industry and the people associated with it. Many notable film studios, such as Columbia Pictures, ...

, where he first accepted a job as a $750/week administrative assistant for motion picture producer Samuel Goldwyn

Samuel Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz; yi, שמואל געלבפֿיש; August 27, 1882 (claimed) January 31, 1974), also known as Samuel Goldfish, was a Polish-born American film producer. He was best known for being the founding contributor a ...

. He was on Goldwyn's payroll until November 1940. In 1939, he set up "Globe Productions", a company to produce short films for penny arcades but the company was liquidated in 1944 while Roosevelt was on active duty with the Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

. Roosevelt also produced the film '' Pot o' Gold'' and distributed the British film ''Pastor Hall

''Pastor Hall'' is a 1940 British drama film directed by Roy Boulting and starring Wilfrid Lawson, Nova Pilbeam, Marius Goring, Seymour Hicks and Bernard Miles. The film is based on the play of the same title by German author Ernst Toller who h ...

''.

During his Hollywood period, Roosevelt became involved with Joseph Schenck

Joseph Michael Schenck (; December 25, 1876 – October 22, 1961) was a Russian-born American film studio executive.

Life and career

Schenck was born to a Jewish family in Rybinsk, Yaroslavl Oblast, Russian Empire. He emigrated to New York City ...

, a movie mogul who was later caught participating in a payoff scheme that was intended to buy peace with movie industry labor unions. In 1942, Schenck pleaded guilty to one count of perjury and spent four months in prison before being paroled. In October 1945, Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

granted Schenck a presidential pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

, a fact which did not become known to the public until 1947.

Military career

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

broke out in Europe in September 1939; the following month Roosevelt resigned the Marine commission as a lieutenant colonel that he had received in 1936 when serving as his father's military aide and accepted a commission as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Marine Corps Reserve so that he could enter active duty, which he did in November 1940.

In April 1941, his father sent him on a secret, world-circling diplomatic mission to assure numerous governments that the United States would soon be in the war. The leaders contacted included Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

in China, King Farouk

Farouk I (; ar, فاروق الأول ''Fārūq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 193 ...

in Egypt, and King George of Greece. During this trip, Roosevelt came under German air attack in both Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. In the African/Middle Eastern portions of the mission, he traveled with Britain's Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

as far as Bathurst in the Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

. They reported on trans-African air ferry conditions, an important concern of FDR and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

at the time. In August, Roosevelt joined the staff of William J. Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat, best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Bur ...

, coordinator of information, with the job of working out the exchange of information with other agencies.

World War II

AfterJapan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

's Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

on December 7, 1941, Roosevelt was seated next to his father when the President delivered his Day of Infamy speech

The "Day of Infamy" speech, sometimes referred to as just ''"The Infamy speech"'', was delivered by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States, to a joint session of Congress on December 8, 1941. The previous day, the Emp ...

. He requested assignment to combat duty and was transferred to the Marine Raiders

The Marine Raiders are special operations forces originally established by the United States Marine Corps during World War II to conduct amphibious light infantry warfare. " Edson's" Raiders of 1st Marine Raider Battalion and " Carlson's" Ra ...

in January 1942, a new Marine Corps commando force, and became second-in-command of the 2nd Raider Battalion under Evans Carlson

Evans Fordyce Carlson (February 26, 1896 – May 27, 1947) was a decorated and retired United States Marine Corps general officer who was the legendary leader of "Carlson's Raiders" during World War II. Many credit Carlson with developing the tac ...

(''Carlson's Raiders'') whom Roosevelt knew when Carlson commanded the Marine detachment at the Warm Springs, Georgia

Warm Springs is a city in Meriwether County, Georgia, United States. The population was 425 at the 2010 census.

History

Warm Springs, originally named Bullochville (after the Bulloch family, which began after Stephen Bullock moved to Meriwether ...

, residence of his father. Roosevelt's influence helped win presidential backing for the Raiders—influenced by the British Commandos—which were opposed by Marine Corps traditionalists.

Despite occasionally debilitating health problems, Roosevelt served with the 2nd Raiders at Midway in early June 1942 and in the Makin Island raid

The Raid on Makin Island (17–18 August 1942) was an attack by the United States Marine Corps Raiders on Japanese military forces on Makin Island (now known as Butaritari) in the Pacific Ocean. The aim was to destroy Imperial Japanese inst ...

on August 17–18, 1942, where he and 22 others were awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

. In October, he was given command of the new 4th Raiders, but during training for an upcoming combat operation he became ill enough to be hospitalized by February 1943. Beginning in August 1943, he served in various staff positions for the duration of the war. He was attached to and landed with the U.S. Army's 165th Regimental Combat Team, 27th infantry Division during the invasion of Makin on November 20–23 and was awarded the Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against an e ...

by the army. He was promoted to colonel on April 13, 1944. He was released from active duty in August 1945 and was placed on the inactive list in October 1945. That same month he became a Compatriot of the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution

The National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR or NSSAR) is an American Congressional charter, congressionally chartered organization, founded in 1889 and headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky, Louisville, Kentucky. A non-prof ...

.

Roosevelt continued in the Marine Corps Reserve and retired on October 1, 1959, with the advanced rank of brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

. Roosevelt suffered from flat feet

Flat feet (also called pes planus or fallen arches) is a postural deformity in which the arches of the foot collapse, with the entire sole of the foot coming into complete or near-complete contact with the ground. Sometimes children are born ...

, and was allowed to wear sneakers while other Marines were required to wear boots.

Military awards

Roosevelt's military decorations and awards include:Navy Cross citation

The Navy Cross is presented to James Roosevelt, Major, U.S. Marine Corps (Reserve), for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service as second in command of the Second Marine Raider Battalion against enemy Japanese armed forces on Makin island. Risking his own life over and above the ordinary call of duty, Major Roosevelt continually exposed himself to intense machine-gun and sniper fire to ensure effective control of operations from the command post. As a result of his successful maintenance of communications with his supporting vessels, two enemy surface ships, whose presence was reported, were destroyed by gun fire. Later during evacuation, he displayed exemplary courage in personally rescuing three men from drowning in the heavy surf. His gallant conduct and his inspiring devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.For the President, '' Chester W. Nimitz''

Silver Star citation

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star (Army Award) to Lieutenant Colonel James R. Roosevelt (MCSN: 0–5477), United States Marine Corps, for gallantry in action at Makin Atoll, Gilbert Islands, 20 to 23 November 1943. Attached as an observer to the units of the 27th Infantry Division which effected the landing on Makin Atoll, Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt voluntarily sought out the scenes of the heaviest fighting. Throughout the three-day period, he continually accompanied the leading elements of the assault, exposing himself to constant danger. His calmness under fire and presence among the foremost elements of the attacking force was a source of inspiration to all ranks.General Orders: Headquarters, U.S. Army Forces, Central Pacific Area, General Orders No. 55 (1944)(26)

Battle stars

LtCol Roosevelt was entitled to campaign participation credit (i.e., the "battle stars

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or ser ...

" worn on the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal) for the following actions:

* Battle of Midway, June 3–6, 1942 (Navy P-7)

* Capture and Defense of Guadalcanal, August 10, 1942 – February 8, 1943 (Navy P-9)

* Makin Raid

The Raid on Makin Island (17–18 August 1942) was an attack by the United States Marine Corps Raiders on Japanese military forces on Makin Island (now known as Butaritari) in the Pacific Ocean. The aim was to destroy Imperial Japanese inst ...

, August 17–18, 1942 (Navy P-10)

* Eastern Mandates November 1943 – January 1944 (Army, for Makin)

Post-war career

AfterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Roosevelt returned to live in California. He rejoined Roosevelt and Sargent as an executive vice president and established the company's office in Los Angeles. In 1946, he became chairman of the board of Roosevelt and Haines, successor to Roosevelt and Sargent. He later became president of Roosevelt and Company, Inc.

On July 21, 1946, Roosevelt became chairman of the California State Democratic Central Committee. He also began making daily radio broadcasts of political commentary. Like his brother Elliott Roosevelt, Roosevelt was prominent in the movement to draft Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

as the Democratic candidate for president in 1948. When President Truman was renominated instead, Roosevelt stepped down as state chairman on August 8. He remained a Democratic National Committeeman until 1952.

In 1950, Roosevelt was the Democratic candidate for Governor of California

The governor of California is the head of government of the U.S. state of California. The governor is the commander-in-chief of the California National Guard and the California State Guard.

Established in the Constitution of California, the g ...

but lost to Republican incumbent Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitution ...

by almost 30% of the votes.Our Campaigns – Candidate – James RooseveltAccessed June 13, 2013 In 1954, Roosevelt was elected U.S. Representative from

California's 26th congressional district

California 26th congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of California currently represented by .

The district is located on the South Coast, comprising most of Ventura County as well as a small portion of Los Ange ...

, a heavily Democratic district. He was re-elected to five additional terms and served from 1955 to 1965, resigning during his sixth term. Roosevelt was one of the first politicians to denounce the tactics of Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

. He was also the only representative to vote against appropriating funds for the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

.

In April 1965, Roosevelt ran for Mayor of Los Angeles

The mayor of the City of Los Angeles is the official head and chief executive officer of Los Angeles. The officeholder is elected for a four-year term and is term limit, limited to serving no more than two terms. (Under the Constitution of Califo ...

, challenging incumbent Sam Yorty

Samuel William Yorty (October 1, 1909 – June 5, 1998) was an American radio host, attorney, and politician from Los Angeles, California. He served as a member of the United States House of Representatives and the California State Assembly, ...

, but lost in the primary.

He resigned from Congress in October 1965, 10 months into his sixth term, when President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

appointed him a delegate to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

). Roosevelt resigned from UNESCO in December 1966 and retired to become an executive of the Investors Overseas Service Investors Overseas Services, Ltd. (IOS) was founded in 1955 by financier Bernard Cornfeld. The company was incorporated outside the United States with funds in Canada and headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland.

In the 1960s, the company employed 2 ...

(IOS) in Geneva, Switzerland.

Roosevelt joined the IOS despite the overseas firm's concurrent investigation by the SEC for numerous irregularities. In Geneva in May 1969, during the unraveling of IOS, Roosevelt's third wife, Irene Owens, stabbed him "eight times" with his "own Marine combat knife" while he was preparing divorce proceedings. When fugitive financier Robert Vesco

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

obtained control of IOS from Bernie Cornfeld and absconded with approximately $200 million, Roosevelt initially stayed on under Vesco. Roosevelt later wrote that "As soon as I saw the situation for what it was, in 1971, I resigned my position." However, this episode resulted in federal charges being laid against Roosevelt and several others, as well as a Swiss arrest warrant. The charges were later dropped and then he returned to California, settling in Newport Beach. He became associated with the Nixon Administration in several capacities and remained friendly with Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

until his death.

Despite having been a liberal Democrat all of his life, Roosevelt joined Democrats for Nixon and publicly supported President Nixon's 1972 re-election and also supported Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

in 1980 and 1984.

His writings include ''Affectionately, FDR'' (with Sidney Shalett, 1959) and ''My Parents, a Differing View'' (with Bill Libby

William Melvin "Bill" Libby (November 14, 1927 – June 17, 1984) was an American writer and biographer best known for books on sports including 65 on sports figures.

Early years

Libby graduated from Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, also at ...

, 1976). The latter was written in part as a response to his brother Elliot's book ''An Untold Story'', which told of FDR's marital issues and was fiercely repudiated by the other siblings. He authored the novel ''A Family Matter'' (with Sam Toperoff, 1979) and edited ''The Liberal Papers'', published in 1962.

Later controversy

In the 1980s, a non-profit organization established by Roosevelt, the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare and its associated political action committee, were investigated by theHouse Ways and Means Committee

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other program ...

for questionable money-raising practices and by the Post Office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional serv ...

for mail fraud. By direct mail, Roosevelt's group solicited contributions from elderly persons by claiming that Social Security and Medicare programs were in financial jeopardy. Roosevelt also urged contributors to order their Social Security statements of earnings from his group (these are free from the government).

Family and marriages

His first marriage was in 1930 to philanthropist Betsey Maria Cushing (1908–1998), the middle daughter of surgeonHarvey Williams Cushing

Harvey Williams Cushing (April 8, 1869 – October 7, 1939) was an American neurosurgeon, pathologist, writer, and draftsman. A pioneer of brain surgery, he was the first exclusive neurosurgeon and the first person to describe Cushing's disease. ...

and Katharine Stone Crowell. They had two daughters, Sara

Sara may refer to:

Arts, media and entertainment Film and television

* ''Sara'' (1992 film), 1992 Iranian film by Dariush Merhjui

* ''Sara'' (1997 film), 1997 Polish film starring Bogusław Linda

* ''Sara'' (2010 film), 2010 Sri Lankan Sinhal ...

(1932–2021) and Kate (b. 1936), before divorcing in 1940. His daughter, Kate Roosevelt, married the Kennedy family

The Kennedy family is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P. J." Kennedy be ...

aide William Haddad and later CEO of the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

Franklin A. Thomas

Franklin Augustine Thomas (May 27, 1934 – December 22, 2021) was an American businessman and philanthropist who was president and CEO of the Ford Foundation from 1979 until 1996. After leaving the foundation, Thomas continued to serve in leade ...

.

James married his nurse, Romelle Therese Schneider (1915–2002), the next year. They had three children, James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

(b. 1945), Michael Anthony (b. 1947), and Anna Eleanor "Anne" (b. 1948). They were divorced in 1956.

In 1956, he married Gladys Irene Owens (1916–1987), his receptionist, and they had a son together named Hall Delano (called "Del") in 1959. They were divorced in 1969.

He married his fourth wife, Mary Winskill (b. 1939), teacher to his youngest son Del, in 1969. They had one daughter, Rebecca Mary, in 1971.Roosevelt, J.: ''My Parents'', passim.

Death

Roosevelt died inNewport Beach, California

Newport Beach is a coastal city in South Orange County, California. Newport Beach is known for swimming and sandy beaches. Newport Harbor once supported maritime industries however today, it is used mostly for recreation. Balboa Island, Newport ...

, in 1991 of complications arising from a stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

and Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms becom ...

. He was 83 and was the last surviving child of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Dates of rank

See also

* Elliott Roosevelt * Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr. *Anna Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

* John Aspinwall Roosevelt II

References

Notes

Bibliography

Brigadier General James Roosevelt, USMCR

''Who's Who in Marine Corps History'', History Division, United States Marine Corps

Retrieved on 2008-07-08

– Marine Corps Legacy Museum * Hansen, Chris. ''Enfant Terrible: The Times and Schemes of General Elliott Roosevelt.'' Tucson: Able Baker Press, 2012. * Roosevelt, James. ''Affectionately, F.D.R.'' Hearst/Avon Division, New York, 1959. (w. Sidney Shalett) * Roosevelt, James. ''My Parents: A Differing View''. Playboy Press, Chicago, 1976. (w. Bill Libby)

External links

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Museum

*

held b

Special Collection & Archives

Nimitz Library

at th

United States Naval Academy

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Roosevelt, James 1907 births 1991 deaths American film producers 20th-century American memoirists 20th-century American novelists United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II American people of Dutch descent American people of Scottish descent Bulloch family Burials at Pacific View Memorial Park Children of presidents of the United States Delano family Harvard College alumni Marine Raiders Livingston family Members of the United States House of Representatives from California New York (state) Democrats Personal secretaries to the President of the United States Recipients of the Navy Cross (United States) Recipients of the Silver Star

James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

Schuyler family

United States Marine Corps generals

United States Marine Corps reservists

Writers from California

Writers from New York City

20th-century American politicians

Military personnel from New York City

Boston University School of Law alumni

Hasty Pudding alumni

Groton School alumni

Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from California

Deaths from Parkinson's disease